Critter Race Theory: Why is your HR department obsessed with evolutionary psychology?

The New Zealand public sector fixation on individualising bias is more than just misguided. It defangs the problem of colonialism and racism that underpins our systems.

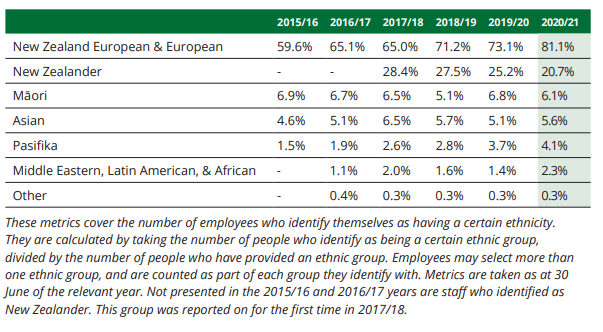

Just over a year ago, following the second anniversary of the March 15 white supremacist terror attack, NZ Security Intelligence Service (NZSIS) boss Rebecca Kitteridge appeared before Parliament’s Security and Intelligence Select Committee. This followed a report from the Royal Commission that there had been an “inappropriate concentration of counter-terrorism resources on the threat of Islamist extremist terrorism” prior to the attack. Kitteridge responded, saying that many staff had undertaken unconscious bias training and she was aiming for a more diverse workforce (the ethnicity breakdown in NZSIS’s 2021 Annual Report is 81% ‘NZ European and European’ and 21% ‘New Zealander’, an identity category favoured by cranky Pākehā who ‘don’t see colour’). ‘Unconscious bias’, along with ‘diversity and inclusion’, has become a catchphrase for organisations ostensibly attempting to interrogate their own racism (sorry, ‘biases’). However, its effectiveness as a lens for interrogating structural racism and colonialism is questionable.

Ethnic diversity within the NZSIS, from 2021 annual report

NZSIS isn’t alone in the way it frames the problem. As organisations like NZ Police, Oranga Tamariki and The Ministry of Health grapple with their own racism, the Public Service Commission has been implementing the Papa Pounamu ‘diversity and inclusion’ work programme. Priority Area 2 of Papa Pounamu: ‘Te Urupare i te Mariu | Addressing Bias’ says organisations “can and should be addressing bias and discrimination in all its forms”. Although this claims to refer to “more than just unconscious bias training”, HR departments around the sector have honed in on unconscious bias as a lens through which to view racism.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

For example, an OIA to the Public Service Commission found that “more than half of agencies are members of Diversity Works NZ.” Diversity Works is a non-profit organisation that offers induction modules to teach new employees about unconscious bias. These modules make no mention of Te Tiriti, colonialism or Te Ao Māori, have a private sector-centric focus on ‘company performance’ and use evolutionary psychology as their basis. Evolutionary psychology is a contentious discipline with historic links to pseudosciences like phrenology, most famously associated today with sentient prolapsed-anus Jordan Peterson. The Diversity Works module posits that unconscious bias is caused when our brains enter something called the ‘critter state’. Needless to say, this highly-individualised, condescending, biologically-deterministic understanding of racism may not actually be the best way for organisations to address their shortcomings.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

It is of little surprise that the public sector has responded to the generations-long call to directly tackle the systemic racism and ongoing colonialism of Aotearoa by tinkering around the edges. It turns the problem into a tick-box exercise that does not need to confront where power: political, social, economic power, lies. Individualising discourse, like that of Diversity Works, is part and parcel of how neoliberalism presents its solutions to society’s most urgent problems. You can convince the public sector that the structural inequalities faced by people – in criminal justice, health, housing, employment, education, etc – are just the result of the tiny ghost of an ancestral rodent that resides in their brain.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

This individualisation is a good fit with HR departments who often serve to protect their organisations from criticism. If a worker is the victim of racism in an organisation, then it is much easier to scapegoat the perpetrator’s unconscious critter brain than interrogate the Crown’s complicity. That perpetrator can say “Whoopsies I did a big stinky unconscious bias! But hey, I’m listening, I’m learning, and I’m taming my inner critter” while the organisation continues to operate unchanged. When Te Arawhiti faced accusations of widespread racism, it downplayed its failures. In its response to the accusations, it acknowledged “individual matters” and reiterated its “commitment to building capability” while experiencing an embarrassingly high turnover of Māori staff. In this way, the individualistic nature of unconscious bias discourse is inherently anti-worker.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

The numerous problems with this direction are significantly accentuated with the absence of Te Tiriti o Waitangi from much ‘unconscious bias’ conversation. A module that makes no mention of the public sector’s responsibilities to honour Te Tiriti is one that explicitly ignores the settler colonial foundations on which it stands. Identifying bias in individuals does little to change how power is still concentrated in the Crown’s favour and ignores the urgent question of Māori self-determination. There have been growing calls from tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti for a Te Tiriti-based constitution to be enacted. This would be based on tikanga as the first law of the land where the promises of Te Tiriti are upheld to allow tino rangatiratanga to be actualised. By latching onto context-free unconscious bias training, the public sector is instead representing the many injustices in Aotearoa as consequences of accidentally poor or passively prejudiced decision-making, which exist in a political vacuum. The Crown’s and sector’s monopoly on power then hides slyly in the background, away from questioning eyes.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

We can’t talk about unconscious bias without recognising the problematic ‘diversity and inclusion’ approach – at least the Western, Pākehā-washed version of it – which is popularly touted as the solution. “Diversity” is descriptive; it does not mean there is any substantiated transference of power and authority. When NZSIS and the Royal Commission responds to the Christchurch mosque terrorist attack by concluding that diversity and cultural competency were needed within the public sector to prevent similar attacks, they are not committing to a project of dismantling the white supremacist ideologies that this settler state is built on. To the Crown and its entities, diversity is useful because it brings “economic and social benefits” and “diversity of thought”. It is deliberately flattening. As described by Eridani Baker, “diluting the vocabulary dilutes the potency of the problem”. Many tangata whenua and Muslims have raised this: that this terror attack took place on land where the Crown has undermined Māori political authority, and white supremacy is normalised and bolstered as a result, is no coincidence.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

Organisations like Diversity Works know that diversity discourse has currency. Papa Pounamu as a programme aims to “address bias” through “cultural competence”, and while many may consider this sensible, it relies on dangerous assumptions. This includes believing that a critical mass of training, development and completion of programmes can have the magical effect of “including everyone”. Unspoken within this is an assumption that Indigenous and marginalised cultures can be reduced to be understood, learnt about, consumed and judged against the status quo, in order to be accorded respect and care. Neoliberalism believes that it can “know” cultural differences, that it can somehow master and manage them (see Avril Bell’s politics of recognition). The damaging Crown-led colonial relations are neutralised as benevolent, comfortably counteracted with awareness and knowledge of so-called diverse perspectives. In the background, as workers individually learn about ‘biases’ through sleek slides and diagrams of the human brain, coloniality surges on.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

As you go through one of these modules, a disembodied narrator may offer little pop psychology ‘facts’ on how to “get around” your “non inclusive ways of thinking”. She may tell you that the mental shortcuts our brain makes to categorise people and information are inherently good, but may need to occasionally be reined in. There is silence on the structural and historical aspects of the prejudices we inherit: the hierarchies we assume are natural, the way we organise society and politics, what we consider real knowledge, the values we assign to cultures and worldviews, what we think is “normal” and what we count as “different”. These are not free from the taint of socialisation and political decisions that are made around and by us. To pretend that “biases” are the result of a purely biological force is to continue fanning the flames of injustices, no matter how concerned Rebecca Kitteridge claims to be.

Screenshot from Diversity Works NZ's unconscious bias module

Nabilah Husna Binte Abdul Rahman is a Malay-Muslim writer and artist from Singapore, living in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. She is doing her PhD at Te Herenga Waka, which looks into Asian solidarities with tangata whenua, and their support of Te Tiriti justice and tino rangatiratanga and mana motuhake movements. In her spare time, she paints and complains about the lack of nasi padang in town.

Jimmy Lanyard is an unexceptional Pākehā public servant from Te Whanganui-a-Tara. While he is not doing Borat impressions for the graduate advisors, he enjoys matching his sneakers with his Barkers suit, drinking almond flat whites and watching supercuts of Air New Zealand safety videos.