Barbie and the Utility of Didactic Art

The movie that is bringing people back to cinemas, the second-highest grossing of 2023 (to-date) and the ‘fun’ half of the double-feature that has been memed into box office success centres around a speech. Towards the end of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, America Ferrara’s hardworking girlmom Gloria turns directly to the camera and delivers a monologue about how hard it is to be a woman in modern society. This speech, necessarily, stops the film in its tracks.

America Ferrera on what it means to be a woman in Barbie.

Until this point, Gerwig’s third solo feature as director, had been an upbeat pop-feminist caper. This colourful, semi-ironic toy advertisement had reminded me more than anything of the camp classics of turn-of-the-century queer cinema (I’m thinking films like D.E.B.S, But I’m a Cheerleader and Josie and the Pussycats). Where those films had been content to subvert the patriarchy from within a veneer of trash, Barbie has more prestigious aims. This is understandable; Gerwig has been an indie-darling long before the critically acclaimed Lady Bird and Little Women. Given its considerable budget, A-list actors and merchandise tie-ins, Barbie couldn’t afford to simply be a cult-classic. Hollywood is famously unforgiving of women directors so for Gerwig to continue her track record, she needed to make a film that was impossible to misunderstand.

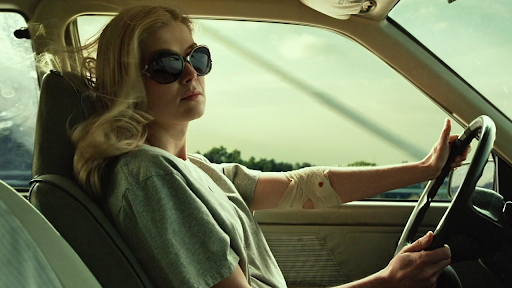

Rosamund Pike on what it means to be a ‘Cool Girl’ in Gone Girl.

The speech, and the film, has become a sensation. Like the (in)famous ‘cool girl’ monologue from Gone Girl, to which it has been compared, it is a manifesto for liberal feminism. During the New Zealand International Film Festival (NZIFF), General Manager Sally Woodfield introduced Bread and Roses, Gaylene Preston’s groundbreaking biopic of union legend Sonja Davies by reading the speech out in full. Your mileage may vary as to whether you found this inspiring, or cringe.

Now regardless of if you liked Barbie (for what it’s worth, and it’s not worth much, I think it’s a solid comedy elevated by Gerwig’s direction and magnetic movie star performances from Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling), there is a limit to how progressive a film made by the Mattel Corporation to sell dolls can be. However, it is not the only recent mainstream film to make direct eye contact with audience members and explain its themes and politics to them. This is particularly galling given the current move in pop culture towards utilitarianism and obviousness. Even works with loftier leftwing aspirations have employed this technique within mainstream film. However, the utility of this approach, and didactic film more generally, is really hard to pin down.

Margot Robbie on sub-prime loans in The Big Short.

When I think of recent films that employ a didactic approach for a broad audience, the one that justifies its approach best is, in my opinion, The Big Short. Because Adam McKay’s movie deals with the incredibly complex use of financial instruments in triggering the 2007 housing market crash, it makes sense for it to hold the audience’s hand. Financial markets are complex by design, that complexity bolsters the power of those who use the markets to enrich themselves and keeps ordinary people out. Therefore, a scene that features Barbie herself explaining sub-prime loans to the audience only serves to reinforce that theme by chipping away at the information asymmetry. McKay’s subsequent films Vice and Don’t Look Up attempt to replicate this didacticism but do so to diminishing returns. Nobody needs Margot Robbie in a bathtub to explain to them that Dick Cheney is heartless or that those in power ignore environmental catastrophe–we get it!

Ariela Barer on why to blow up a pipeline in How to Blow Up a Pipeline.

Another film that screened at NZIFF, How to Blow up a Pipeline does what it says on the tin. A mostly effective adaptation of Andreas Malm’s 2021 book, it argues that people have a moral imperative to destroy fossil fuel infrastructure. Alternating showing (a thrilling series of events in which the motley crew of young activists undertake the titular direct action) with telling (flashbacks in which each character realises, and verbalises, that respectable avenues of climate action have failed), it makes a decent case for its own didacticism. Would it be a better movie were it a straightforward procedural? Probably, but then it might not be as effective at inspiring people to take action. Having said that, I struggle to imagine how a film about the limits of electoralism could ever provide sufficient explanation to sway the guy at my screening who yelled “party vote Green!” when the lights came up.

Kara Young on the crisis of capitalism in I’m a Virgo.

This is the tension at the heart of most of these movies. The things that make a film better, often make it less useful as activism. Think of Judas and the Black Messiah, an excellent thriller about the betrayal and murder of Fred Hampton that was criticised by many on the left as downplaying Hampton’s revolutionary politics. Would these critics be happy if Daniel Kaluuya turned directly to the camera and explained to the audience the intertwined relationship between white supremacy and capitalism (like Boots Riley has Kara Young do in I’m a Virgo)? Maybe, but that would surely undermine its strengths as a piece of genre filmmaking.

If films typically lie downstream from politics and their ability to affect change is nebulous, many leftists conclude that it’s a fool’s errand to even take politics into account with film criticism. The result has been a resurgent celebration of reactionary art (ironic, performative or genuine). If the Obama years were characterised by the liberal idea that you could affect change just by consuming enough content with good politics, the years since then have seen a pendulum swing in the other direction for many socially-conscious cinephiles. Well-made right-wing films like Top Gun: Maverick and RRR are darlings on film Twitter even (especially) among leftists, while Don’t Look Up is treated like a punchline. The logical conclusion of this is the type of vulgar auteurism that elevates filmmakers like Michael Bay whose shilling for the American Empire is at least packaged competently. A more reasonable example can be seen in Movie Mindset, the recent film criticism podcast in which left-Twitter mainstays Will Menaker and Hesse Deni dedicate episodes to Tony Scott and Clint Eastwood respectively. These filmmakers carry an undeniable appeal to Menaker and Hesse even as they grapple with the more noxious aspects of their politics.

Effective art is often characterised by ambiguity, moral greyness and openness to interpretation. Effective propaganda, on the other hand, tends to be didactic, direct and utilitarian. Sure, there are plenty of films that manage to balance these competing demands (such as The Battle of Algiers) but the need to entertain someone often sits uneasily with the need to influence their behaviour. I’m certainly not inclined to disregard activist filmmaking entirely, or any of the aforementioned films, even when they are annoying. However, there are dozens of films that I love whose politics I struggle with, if not outright reject. If art helps us make sense of the world, there’s certainly a place for both approaches, even if Barbie won’t actually bring down the patriarchy.

Jimmy Lanyard is an unexceptional Pākehā public servant from Te Whanganui-a-Tara. While he is not doing Borat impressions for the graduate advisors, he enjoys matching his sneakers with his Barkers suit, drinking almond flat whites and watching supercuts of Air New Zealand safety videos. Listen to Jimmy talk about film on Dinner and a Movie podcast with Nabilah Husna Binte Abdul Rahman.